|

|

THE COMMITTEE OF SLEEP: DREAMS AND CREATIVE PROBLEM SOLVING ©2007 Deirdre Barrett, Ph.D.

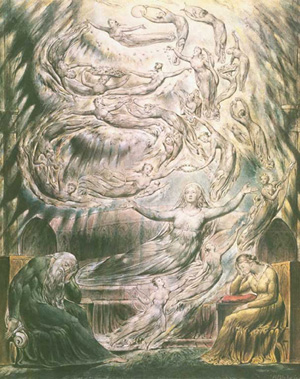

I took the title of this paper and one of my books from Steinbeck's quote because it so well sums up nature of the unconscious generally and dreams specifically. The unconscious is not one type of thinking, but rather any part of self that’s not conscious—and these can all can show up in dreams. The major concerns of dreaming are obviously our personal issues--childhood slights, current moods, and how we get along with significant others. However, these aspects of dreaming are covered thoroughly by most other dream psychologists, so I’ve become interested in objective problems in dreams--the scientific and artistic. It’s fascinating that they happen, and they can tell us something about dreaming on personal issues because they’re easier to quantify and study. In this paper I want to offer some of the most dramatic anecdotes from a variety of fields—both ones that appeared in The Committee of Sleep (Barrett, 2001) and others—and draw some generalizations from patterns of such dreams. Arts and Design More dream inspirations occur in the visual arts than any other, as visual imagery occupies so much of the content of dreaming German artist Albrecht Durer’s 1525 watercolor of a savage storm bears the following inscription: I saw this image in my sleep, how many great waters poured from heaven... drowning the whole land... The deluge fell with such frightening swiftness, wind, and roaring that when I awoke, my whole body trembled; for a long while I could not come to myself. So when I arose in the morning, I painted what I had seen. Visionary William Blake portrayed dreams of Queen Catherine and Biblical Jacob in his distinctive mystic style, characters soaring through the heavens. He painted his own as "Young Night's Thoughts” (1818) with himself lying on the ground dreaming, the action of the dream painted next to him, a poem based on the same dream beneath that, and finally a straightforward account of the dream.

Blake also had recurring dreams of a supernatural art instructor, with a third eye in his forehead. The instructor showed Blake images to paint and advised him on technique. Awake, Blake made numerous oil colors of the recommended scenes. He sketched the teacher in the straightforwardly titled, "Man Who Instructed Blake in Painting in His Dreams.”(1819) Pre-Raphaelite Sir Edward Burne-Jones painted scenes of medieval knights and ladies dreaming about each other. Traveling to Rome by train, the artist fell asleep and dreamed of the nine muses on Mt. Helicon so vividly that he felt compelled to paint them the moment he arrived at his destination. Burne-Jones wrote of this painting, “The Rose Bower” (1870-90), “I meant to depict a beautiful dream...in a light better than any light that ever shone. . . in a land no one can remember. . .”

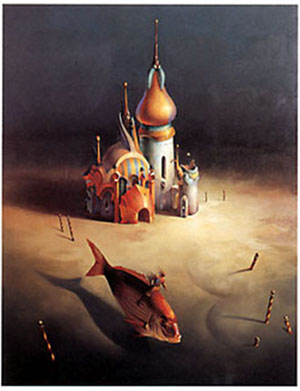

Many surrealists painted specific dream images, and all of them used characteristics of the dream world such as space that has no depth or extends to infinity, and juxtaposition of objects which don’t belong together. A few titles which reflect this are: Salvador Dali’s “The Dream;” Frida Kahlo’s painting of the same name; Max Ernst’s “Dream of a Girl Chased by a Nightingale;” Paul Nash’s “Landscape from a Dream;” Dali’s “The Dream Approaches;” and Gil Bruvel’s “The Sleep Goes Away.”

...and

One modern example from people I interviewed is that of the chief architect at a major firm who describes solving many design problems on which she is stuck by dreaming of being inside the finished building. She notes—as if remembering--how she solved the problem: I've designed at least a dozen to 15 houses this way. It typically happens when I've worked on a project, but I'm not really getting anywhere. Those tend to be the ones that pop out in the dream process. I remember one house I was kind of stuck on and I had a dream that I went to a party in the finished house--that solved it! It was an incidental detail to the dream, but crucial to waking life. (Barrett, 2001, p.17) Dreams have frequently contributed to literature, narrative being the second most prominent element of dreaming after visual imagery. In 1816, when Mary Wollstonecraft and other houseguests of Lord Byron had told ghost stories and then agreed they should each write their own, she retired and dreamed: I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together--I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. He would hope that, left to itself, the slight spark of life which he had communicated would fade. He sleeps but he is awakened; he opens his eyes, behold, the horrid thing stands at his bed side, opening his curtain and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes. Swift as light and cheering was the idea that broke in upon me. ”I have found it! What terrified me will terrify others, and I need only describe the specter which had haunted my midnight pillow.” On the morrow I announced I had thought of the story. The dream, of course, became the classic horror story of all time, Frankenstein. The teenage author was pregnant by Shelley at the time of the dream, so the creation of a wondrous, monstrous entity undoubtedly had immense unconscious significance. However, the Committee combined her personal issue with Byron’s casual challenge into a creation which transcended both. Man has consulted his nocturnal muse for as long as he has sought tales to entertain his peers. In fifth century AD Synesius of Cyrene observed, “How often dreams have come to my assistance in the composition of my writings! They aided me to put my ideas in order and my style in harmony with my ideas; they have made me expunge certain expressions, and choose others. When I allowed myself to use images and pompous expressions, in imitation of the new Attic style (a ‘modern’ fad which disappeared by sixth century AD--author)...a god warned me in my sleep, censuring my writings, and making the affected phrases to disappear, brought me back to a natural style.” The Romantic writers were especially fond of dreams. Mary’s husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley published a collection of his nocturnal experiences in The Catalogue of Phenomenon of Dreams, as Connecting Sleeping and Waking. Cristina Rosetti, whose painter husband was inspired by dream imagery, used hers in poetry such as “The Crocodiles” which described a fanciful version of the animal encrusted with gold and polished stones. Modern writers who have written scenes from dreams include Anne Rice, Stephen King, Eudora Welty and Jack Kerouac.

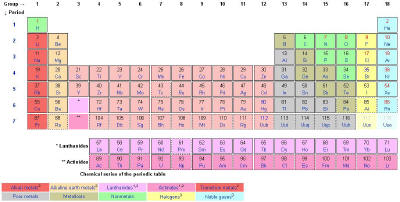

Science A dream of August Kekulé may be the oft-most quoted science example. After recounting an earlier dream which contained the inspiration for his “Structural Theory”, precursor to modern organic chemistry, Kekulé moved on to describe the dream that came to him when he was stuck on figuring out the structure of the benzene molecule when at the time all known molecules were straight lines with side-chains: Again the atoms were gamboling before my eyes . . . rendered more acute by repeated visions of the kind, I could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: of rows, sometimes more closely fitted together all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis. (Kekulé, 1890) Kekulé makes it clear that his “snake” was a string of atoms and that the solution came within the dream. Biologist Margie Profet dreamed an entire cartoon demonstrating an idea for which she subsequently won a McArthur “genius” grant. She said, “My Mom first told me about menstruation when I was seven. I thought it was the weirdest thing I’d ever heard of. When I was 10 or 11, the school gave information about reproduction to girls. They’d send the boys away. They had a film with cartoon drawings of a woman’s body with ovaries and fallopian tubes. In the cartoon, there was the uterine lining building up and the egg being released. Then it ended with this thing, like, if there’s no pregnancy, it just gets rid of everything. A red flag went up and I thought, ‘That doesn’t make sense!'” Biology explained this major loss of blood, tissue, and nutrients as an inefficient part of the reproductive process. By the spring of 1989, Profet had become a biologist. She’d done work on pregnancy sickness, but had never considered studying menstruation. While conducting allergy research, she had the following dream: In the dream I saw cartoon images of a woman’s body, like the ones in the school film. The ovaries were pale yellow; the uterus was deep red. There were black triangles in the endometrium. Blood was coming out, taking the triangles with it. Then my cat meowed, wanting out--he was quite a nocturnal hunter. I woke up into this half-awake state and thought, “The black things are pathogens--that’s why!” I went back to sleep. The next morning I had this vague feeling, “Did I have a dream last night?” I wandered around and then, “Oh yeah!” “That dream completely changed the course of my research,” Profet recalls. “I finished the allergy studies, of course, but then I spent the next three years studying menstruation.” Profet's dream-inspired theory posits that harmful bacteria enter the womb and Fallopian tubes attached to sperm. Menstruation eliminates the threatening intruders in two ways: the sloughed-off uterine lining carries microbes off, and the blood itself is rich in immune cells ready to engulf pathogens. Profet buttressed her theory with two electron-microscopy studies. One detected bacteria attached to the heads and tails of wriggling sperm. The other showed the rich supply of macrophage immune cells in menstrual blood--very much as in her dream. Profet's theory and research earned her a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant. Media outlets covered the story of her perceptive insight and her work to prove it correct. "It's the only serious contender for a plausible evolutionary explanation of menstruation,” says George Williams, an editor at the Quarterly Review of Biology. "It is extremely unlikely that her theory is seriously wrong. Her arguments are quite convincing." Physiologist Otto Loewi won the 1936 The Nobel Prize for an experiment he’d first visualized in his sleep—probably a dream. (Loewi, 1960) Demitri Mendeleev was struggled to find a way to classify chemical elements by traits like their atomic weight and valence. One night after working on the problem, he fell asleep and “saw in a dream a table where all the elements fell into place as required.” The table of his dream is now the Periodic Table of the Elements. (Kedrov, 1957) When I interviewed scientists about their dreams for a trade book, I got examples of inventions such as new computer designs and numerous computer programs. One programmer told me, “When I’m working on a project, I tend to dream about it. I’ll even dream in computer language: C++ is what I use to program. More often the dreams solve smaller parts of a problem.” He gave the following example of a dream about a program which would allocate computer memory to complex matrices with which he worked: The data was floating around in three-dimensional space. I was seeing abstract geometric shapes with numbers in them--floating, twisting, coming around to the arrangements in which they needed to be. At the same time, I knew what the algorithm had to be in order to achieve this. It would need to use a method called ‘recursion’ where you break a large problem into smaller problems repeatedly. All the details were in the dream. When I woke up, I went to my computer and did it just as in the dream--and it worked! (Barrett, 2001, p. 103) A physicist who designs the controls for telescopes described how he got unstuck from problems: “Often I’d have a dream. These problem solving dreams are not like my others. I’m simply an observer. They have a lot of clarity--there’s not the bizarreness of other dreams. These dreams have a narrator who’s sketching the problem verbally. Then the voice is giving the solution. I’m also seeing the solution. I watch a man working on the mechanical device--arranging lenses for the optics or building the circuit--whatever it is that I’m stuck on at that point. The dream always takes it a slightly different way from what we’ve been trying awake. . . . I take my notes into work and tell my team ‘I’ve dreamed up a solution---literally.’ They’ve gotten quite used to doing things from my dreams.” (Barrett, 2001, p. 108-109) Other Objective Fields Not all dream problem-solving is about science or art. Even within the realm of objective professional issues, Jack Nicklaus dreamed of a new way of holding his golf club that greatly improved his game. (Barrett, 2001, p. 138) Acrobat Tito Gaona became the first person ever to perform the “double-double”—a double forward somersault with two full side turns executed at the same time—after he experienced himself doing it in a dream. (Barrett, 2001, p. 139) And in another solved-at-start-of-dream example, a professional magician described how he became one of a handful of people in the world who knew the secret of Houdini’s “Dissolving Cards” trick. After simply hearing a description of its appearance to the audience, he dreamed: A magician was performing the trick. As I witnessed it, a voice was telling me how it was done. And I could see exactly how and why it must work! I just stared in amazement. The concept was so simple but it worked only when the execution and timing were flawless. I awoke with no question in my mind that this was what the magician my friend had watched--and indeed--Houdini had done. Although a few people lie or exaggerate the extent to which a dream was their inspiration—Coleridge’s Kubla Khan seems to owe more of its content to waking revisions than his initial description--many problem-solving dreamers are in settings where they would hardly gain by attributing ideas to a dream. World War II General George Patton awakened his secretary repeatedly to dictate battle plans he’d just seen in as dream. During the Battle of the Bulge, he carried out a dreamed surprise attack on German troops as they prepared for an offensive against allies on Christmas Day. (Barrett, 2001) Such successes were welcomed by the military despite--not because of--their source. The creative power of dreaming is regularly discovered anew by ordinary people naïve to its history. A recent exchange on the Internet news group, rec.crafts.textiles.quilting, proceeded as follows: It seems whenever I have a problem with a quilt, or am really engrossed with it, I dream the problem out. To my amazement, most of the problems were solved that way. -Rita This is interesting. I have never dreamt about solving quilt problems, but when I was in high school and in college (25+ years apart), I would solve math and chemistry problems in my sleep. I would go to sleep thinking (obsessing) about the problem and would wake up knowing how to solve it. This worked great! -Patty All this talk about dreams is too much to keep quiet about. So far, I haven’t dreamed about a quilt or chemistry--but when I was eight, I was learning to ride a bike. All day long I got on, fell off--on and off. That night I went to sleep and dreamed I was riding my bicycle. As soon as I woke up, I ran out and just knew I could ride it. I jumped on and didn’t fall off all day long. -Vince These examples are not as dramatic as the professional examples, but they echo several of the patterns from those. The dialogue begins with by someone getting visual designs from dreams—these really are the most common. But virtually anything—math, music or science can appears when someone focuses strongly on that. Dreams present most solutions visually (The benzene ring structure, Profet's cartoon bacteria). Verbal ones may employ puns or charades. Personified helpers often do the honors as with the man who taught Blake painting or the astronomer's telescope builder. Some writers have glamorized dreaming as wiser than waking thought. Others characterize it as useless nonsense. I think these anecdotes demonstrate that it is neither consistently wise nor consistently useless. The dreams power lies in the fact that it is so different a mode of thought—that it supplements and enriches what we’ve already done while awake. REFERENCES Barrett, Deirdre (2001) The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists and Athletes Use Their Dreams for Creative Problem Solving . . .and How You Can, Too. NY, NY: Crown/Random House. Barrett, Deirdre (1993) The “Committee of Sleep”: A Study of Dream Incubation for Problem Solving. DREAMING: The Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams, 3, No. 2. Kedrov, B. M. (1957) On the Question of Scientific Creativity. Volprosy Psikologii 3, p. 91-11, quoted in S. LaBerge Lucid Dreaming, Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher, 1985. Kekulé, August (1890) Benzolfest-Rede. Bericht der Deirschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 23 1302-11, trans. O. T. Benfry, Journal of Chemical Education, 35. Loewi, Otto (1960) An Autobiographical Sketch Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Autumn, as quoted in Edwin Diamond The Science of Dreams, New York: McFadden, 1963, p. 155. Miles, Barry (1997) Paul McCartney—Many Years from Now New York: Henry Holt. Public Broadcasting System (1994) The Power of Dreams,” television documentary, Close window to return to the bulletin board

|

| IASD Home Page | PsiberDreaming Home |

The French Surrealist poet, St. Paul Boux, would hang a sign on his bedroom door before retiring which read: "Poet at work." A similar belief in nocturnal productivity was expressed by John Steinbeck: "It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it."

The French Surrealist poet, St. Paul Boux, would hang a sign on his bedroom door before retiring which read: "Poet at work." A similar belief in nocturnal productivity was expressed by John Steinbeck: "It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it."

Music also has arrived in dreams. Musicians Billy Joel and Joseph Shabalala say they “hear” all their compositions—minus words--in dreams. (PBS, 1994; Time, 1987) More typically, Paul McCartney dreamed “Yesterday”—the most played song in the history of radio. Because of McCartney’s unfamiliarity with the experience, he went around checking with people whether it was a known piece of music. “Because I’d dreamed it, I couldn’t believe I’d written it,” he recalled. (Miles, 1997, p.201)

Music also has arrived in dreams. Musicians Billy Joel and Joseph Shabalala say they “hear” all their compositions—minus words--in dreams. (PBS, 1994; Time, 1987) More typically, Paul McCartney dreamed “Yesterday”—the most played song in the history of radio. Because of McCartney’s unfamiliarity with the experience, he went around checking with people whether it was a known piece of music. “Because I’d dreamed it, I couldn’t believe I’d written it,” he recalled. (Miles, 1997, p.201)