According to Vine Deloria Jr. (2000), a sacred site has the “ability to short-circuit logical process; it allows us to apprehend underlining unities” (p. 30). Rudolf Otto (1924) used the term “numinous” when discussing such properties of holy places. According to some Native American traditions, one experiences these “underlining unities” by participating in rituals at sacred places or by entering these sites while in an altered state of consciousness. Participants often claim to experience unification with nature, a feeling of bliss, interspecies communication, waking visions, unusual sounds, synchronicities, key memories, and/or various ecstasies (Swan, 1988). Another common theme of experiences at sacred sites is “the disappearance or transformation of familiar apprehensions of time and space” (Deloria, 2000, p. 35).

Deward Walker (1996), in describing the value of sacred sites, employed the concept “portal to the sacred.” These alleged portals are trans-dimensional and cross-temporal “such that they become sacred times and spaces” to members of various cultural groups, even if those groups are separated in time (p. 63). Carole Crumley (1999) similarly observed that in many cultures sacred places are considered liminal; tucked between the mundane and spirit world, they are felt to be entry points into another consciousness.

This view of sacred place is particularly well exemplified in the Hindu concept of the tirtha. This word derives from a Sanskrit verb meaning ”to cross over,” generally signifying a path or a passage; when applied to Hindu holy pilgrimage places (typically situated on rivers) it means “a crossing place”. This is not only physically descriptive of many such places but is also deeply metaphorical (Devereux, 2000, p.24; Eck, 1981).

Many Native American traditions attributed similar properties to sacred sites, such as encounters with spiritual agencies during nighttime dreaming (Krippner & Thompson, 1996), a conception shared by traditional cultures in Europe and other parts of the world. In commenting on these traditions, Paul Devereux (1997) has suggested treating prehistory as analogous to the human unconscious; “sacred places, it is suggested, may be those [that] yield greater information than secular ones; [they may be] locations where information is received more effectively by the unconscious mind” (p. 527).

The designation of a site as “sacred” may result from its use as a crossing place or ford (Crumley, 1999) or due to a discontinuity in the landscape, such as a sudden canyon, a shaft of white quartz, or a jagged peak (Walker, 1996). Conversely, a sacred site might be the location of an alleged or actual spiritual event (a place where spiritual entities allegedly appeared, where a prophet was born or died, or where a sage’s “enlightenment” or “awakening” took place). Another possibility is that the geophysical qualities of the location affected people’s thoughts, feelings, and/or perceptions. Strabo (64 BCE-25 CE) wrote that the famed Oracle of Delphi breathed “vapor” from an opening in the earth before making her prophecies, an observation supported by recent archeological research (Hale, de Boer, Chanton, & Spiller, 2003). Traditional beliefs attributed these changed phenomenological states to occult powers, rather than to natural causes. For example, the Mescalero Apaches felt that a force known as diya’ characterized intersections between the physical and spiritual worlds and that spiritual transformation could occur as people spent time in these locations (Carmichael, 1994).

Transformation of one sort or another was sought through the practice of “temple sleep” in a place of worship or in a venerated natural site, with the aim of “incubating” dreams for initiation, divination, or healing purposes. Ancient Jewish seers would spend the night in a grave or sepulchral vault, hoping that the spirit of the deceased would appear in a dream and offer information of guidance. Chinese incubation temples, where state officials would seek guidance, were active until the 16th century. In Japan, the emperor had a dream hall in his palace where he would sleep on a polished stone bed when he needed assistance in resolving a matter of state. Dynastic Egypt had special temples for suppliants who would fast and recite prayers immediately before going to sleep. Before Thutmose IV (c. 1419-1386 PCE) became ruler of Egypt, he related how the god Hormakhu appeared in a dream, foretelling of a united kingdom that would follow his ascension to power. When this came to pass, Thutmose IV recorded the dream on a pillar of stone that still stands before the Sphinx. Temple sleep was also was popular in ancient Greece where over 300 dream temples were dedicated to Aesculapius, the god of healing (Devereux, 2004).

Transformation of one sort or another was sought through the practice of “temple sleep” in a place of worship or in a venerated natural site, with the aim of “incubating” dreams for initiation, divination, or healing purposes. Ancient Jewish seers would spend the night in a grave or sepulchral vault, hoping that the spirit of the deceased would appear in a dream and offer information of guidance. Chinese incubation temples, where state officials would seek guidance, were active until the 16th century. In Japan, the emperor had a dream hall in his palace where he would sleep on a polished stone bed when he needed assistance in resolving a matter of state. Dynastic Egypt had special temples for suppliants who would fast and recite prayers immediately before going to sleep. Before Thutmose IV (c. 1419-1386 PCE) became ruler of Egypt, he related how the god Hormakhu appeared in a dream, foretelling of a united kingdom that would follow his ascension to power. When this came to pass, Thutmose IV recorded the dream on a pillar of stone that still stands before the Sphinx. Temple sleep was also was popular in ancient Greece where over 300 dream temples were dedicated to Aesculapius, the god of healing (Devereux, 2004).

Aesculapius Dream Temple

Even though the possible connection between sacred sites and dreaming has not been studied by Western science, there is a psychological literature regarding environmental influences on dreams. External stimuli may modify dream content, as when an externally administered spray of water is incorporated into a dream about a rainstorm, or cooling the feet by an external agent becomes associated with a dream of ice climbing in the polar regions. These examples have been observed in sleep laboratories, but in a dreamer's ordinary surroundings, the sound of a doorbell may evoke a dream in which a telephone is ringing (Antrobus, 1993).

Given the difficulty in establishing a linear connection between daily events and dream content (e.g., Roussy et al., 2000), it is not surprising that immediate presleep experiences do not make a dependable impact on dream content. For example, viewing erotic films before falling asleep is not inevitably followed by blatantly sexual dreams (Cartwright, Berniche, Borowitz, & Kling, 1969). In one study, only 5% of dream reports reflected incorporation of presleep exposure to violent films (Foulkes & Rechtschaffen, 1964), but other investigators reported a higher percentage when putative symbolic material was included in the analysis (Witkin & Lewis, 1963). However, in another study, a 24-hour fluid restriction was following by references to drinking in one third of the dream reports (Dement & Wolpert, 1956). Stimuli presented during sleep in front of eyes that had been taped open are rarely incorporated into dreams (Rechtschaffen & Foulkes, 1965). However, tones, light flashes, cold water stimuli, and wrist shocks during rapid eye movement sleep were incorporated into 9%, 24%, 47%, and 20% of dream reports, respectively; even so, they were momentary events rather than dream themes (Dement & Wolpert, 1956).

The dreamer's environment may alter dream content; Okuma, Fukuma, and Kobayashi (1975) found that sleeping in an unnatural setting may severely limit and restrict dream data. The dream reports they collected in a sleep laboratory were more mundane than dreams collected by the same research participants in their home surroundings. Therefore, overall it can be said that external stimuli prior to dreaming does not always have a statistically significant influence on dream content. But external stimuli during dreaming may be incorporated into dream content.

Anomalous external effects in dreams (so-called “dream telepathy”) have been reported in some parapsychologically oriented studies (e.g., Krippner, Honorton, Ullman, Masters, & Houston, 1971) but not in others (e.g., Foulkes, Belvedere, Masters, Houston, & Krippner, 1972). Stanley Krippner and Michael Bova (1974) explored the effects of unusual indoor architectural environments on shifts in consciousness and anomalous information retrieval obtaining provocative results; however, nighttime dreams were not one of the altered states investigated. Nevertheless, the experimental design utilized by Krippner and Bova served as a model for some of the procedures adopted by this study.

Hypothesis:

It was hypothesized that, following an analysis of each dream report using the Hall-Van de Castle Scale, the content of dream reports from purported outdoor "sacred sites" would differ significantly from the content of dream reports collected by participants in their homes.

Research participants:

Under the auspices of the Dragon Project Trust, Paul Devereux (PD) recruited volunteer research participants (22 women, 13 men) by word-of-mouth. The volunteers ranged in age from teenagers to sixty-year-olds, came from varied backgrounds, and did not know one another socially. However, they did know of the experimenters’ interest in sacred sites, hence had some idea as to the purpose of the study.

Between 1993 and 1995, several volunteers spent one or more nights at a sacred site, but did not contribute home dream reports, and hence were eliminated from the study. Also eliminated were volunteers who contributed home dreams but never dreamed at a site. The remaining 35 research participants contributed between 1 and 8 pairs of dreams. Male and female data were combined because there were not enough of either to justify separate analyses.

Settings:

Paul Devereux (PD) selected one site in Preseli, a hill range in Wales, and three sites in Cornwall, England, as settings for this study. The sites were selected not only on the basis of their prominence in local folklore, but because they easily afforded space for a volunteer to sleep comfortably in a sleeping bag and/or blankets during the night. The sites selected were Carn Ingli, Carn Euny, Chun Quoit, and Madron Well.

Carn Ingli (“Peak of Angels”) is a jagged peak in the Preseli range, Wales, making it a prominent landmark. Preseli has been geologically identified as the source area for the “bluestones” of Stonehenge. Remnants of low, loose stone walls draped around the Carn Ingli peak may be evidence of veneration of the site in Neolithic or even Mesolithic times. In the 6th century, St. Brynach used the peak as a fasting and meditation retreat and claimed to have spoken with angels there. A local journalist learned of an incident in which a woman was thrown into an involuntary trance state on Carn Ingli and he reported it to the Dragon Project Trust. Its investigators subsequently detected full compass deflections on some of the rock surfaces, as well as in mid-air. Random checks at other peaks along the Preseli range did not produce similar findings (Devereux, Steele, & Kubrin, 1989). There is some evidence that the megalith builders made specific use of magnetic stones in the construction of some of their monuments (Ibid., Devereux, 1999, p. 155), and such devices as Geiger counters have been utilized as investigative tools among archeologists intrigued by possible radioactive and ultrasonic properties of the sites (Sheeran, 1990).

Carn Ingli (“Peak of Angels”) is a jagged peak in the Preseli range, Wales, making it a prominent landmark. Preseli has been geologically identified as the source area for the “bluestones” of Stonehenge. Remnants of low, loose stone walls draped around the Carn Ingli peak may be evidence of veneration of the site in Neolithic or even Mesolithic times. In the 6th century, St. Brynach used the peak as a fasting and meditation retreat and claimed to have spoken with angels there. A local journalist learned of an incident in which a woman was thrown into an involuntary trance state on Carn Ingli and he reported it to the Dragon Project Trust. Its investigators subsequently detected full compass deflections on some of the rock surfaces, as well as in mid-air. Random checks at other peaks along the Preseli range did not produce similar findings (Devereux, Steele, & Kubrin, 1989). There is some evidence that the megalith builders made specific use of magnetic stones in the construction of some of their monuments (Ibid., Devereux, 1999, p. 155), and such devices as Geiger counters have been utilized as investigative tools among archeologists intrigued by possible radioactive and ultrasonic properties of the sites (Sheeran, 1990).

Carn Euny is an Iron Age subterranean structure dating to c.500 B.C. in the Land’s End District of Cornwall. It consists of a stone passageway adjoining a corbelled “beehive” stone chamber. It is one of a class of structures archeologically referred to as “souterrains” or, in Cornish dialect, “fogous”. Their function is unknown, and hypotheses have ranged from food storage to refuges to ritual chambers. The beehive chamber at Carn Euny is an unusual feature, though, and favors a ritual or ceremonial explanation. Because it is an enclosed structure made from blocks of granite, a naturally radioactive rock, its interior has higher levels of radiation than the outside base level. Archaeoacoustical research has also shown the chamber at Carn Euny to have a primary resonant frequency of 99 Hz, within the baritone range of the human voice (Jahn, et al. 1996).

Carn Euny is an Iron Age subterranean structure dating to c.500 B.C. in the Land’s End District of Cornwall. It consists of a stone passageway adjoining a corbelled “beehive” stone chamber. It is one of a class of structures archeologically referred to as “souterrains” or, in Cornish dialect, “fogous”. Their function is unknown, and hypotheses have ranged from food storage to refuges to ritual chambers. The beehive chamber at Carn Euny is an unusual feature, though, and favors a ritual or ceremonial explanation. Because it is an enclosed structure made from blocks of granite, a naturally radioactive rock, its interior has higher levels of radiation than the outside base level. Archaeoacoustical research has also shown the chamber at Carn Euny to have a primary resonant frequency of 99 Hz, within the baritone range of the human voice (Jahn, et al. 1996).

Chun Quoit, also in Land’s End, Cornwall, is an isolated mushroom-shaped monument consisting of four inward-leaning slabs supporting a capstone, and dates to c. 3,000 B.C. It is of a monument type known as a “dolmen” and is located on a broad expanse of high moorland in exactly the right position for the midwinter sun to appear to set in a notch of the natural outcrop that stands prominently on the southwestern skyline. There have been reports of short bursts of light flashing across the underside of the capstone, and Geiger-counter readings have detected high readings for radioactivity (Devereux, 1999, pp. 154-155; Devereux, 1992, pp. 175-183). Again, archaeoacoustical research at this site has revealed a primary acoustical resonance of 110 Hz – well within the baritone range (Ibid., Jahn, 1996). Recent neurophysiological research indicates that sound in the 95-125 Hz range can affect brain function in the frontal and temporal cortex (Cook, 2003; Devereux, forthcoming). This effect is most marked at 110 Hz.

Chun Quoit, also in Land’s End, Cornwall, is an isolated mushroom-shaped monument consisting of four inward-leaning slabs supporting a capstone, and dates to c. 3,000 B.C. It is of a monument type known as a “dolmen” and is located on a broad expanse of high moorland in exactly the right position for the midwinter sun to appear to set in a notch of the natural outcrop that stands prominently on the southwestern skyline. There have been reports of short bursts of light flashing across the underside of the capstone, and Geiger-counter readings have detected high readings for radioactivity (Devereux, 1999, pp. 154-155; Devereux, 1992, pp. 175-183). Again, archaeoacoustical research at this site has revealed a primary acoustical resonance of 110 Hz – well within the baritone range (Ibid., Jahn, 1996). Recent neurophysiological research indicates that sound in the 95-125 Hz range can affect brain function in the frontal and temporal cortex (Cook, 2003; Devereux, forthcoming). This effect is most marked at 110 Hz.

Madron Well, likewise in Land’s End, was once surrounded by massive blocks of granite (according to a 1910 photograph) and is located near the ruins of a medieval granite chapel. The footpath through the woods is like a magical, green-hued walk redolent of former times and beliefs. By the time the visitor reaches the turning for the well on the left, the 20th century seems far away. Traditionally, this site has been associated with “feminine energy.” Up until about the 17th century, a local “wise woman” attended the actual spring. The spring water continues to be fed by stone conduit into a stone reservoir in the chapel’s southwest corner. Madron Well was celebrated for its purported healing properties and oracular powers, and part of the traditional healing procedure involved the patient sleeping within the chapel, one of the few documented cases of ostensibly Christian dream incubation in England. Presumably because it passes through granite conduits, and is deposited into a granite reservoir, the water gives above-background radiation readings. In the 1600s a celebrated and documented case of healing took place here, when John Trelille allegedly became able-bodied after being crippled for 16 years. He was bathed in the waters at the chapel once a week for three weeks, after which time he appeared to be fully healed, and went on to live an active life as a soldier. The very essence of Celtic Christianity, with its powerful Pagan ancestry, seems to be here (Devereux, 1999, pp. 156-157).

Madron Well, likewise in Land’s End, was once surrounded by massive blocks of granite (according to a 1910 photograph) and is located near the ruins of a medieval granite chapel. The footpath through the woods is like a magical, green-hued walk redolent of former times and beliefs. By the time the visitor reaches the turning for the well on the left, the 20th century seems far away. Traditionally, this site has been associated with “feminine energy.” Up until about the 17th century, a local “wise woman” attended the actual spring. The spring water continues to be fed by stone conduit into a stone reservoir in the chapel’s southwest corner. Madron Well was celebrated for its purported healing properties and oracular powers, and part of the traditional healing procedure involved the patient sleeping within the chapel, one of the few documented cases of ostensibly Christian dream incubation in England. Presumably because it passes through granite conduits, and is deposited into a granite reservoir, the water gives above-background radiation readings. In the 1600s a celebrated and documented case of healing took place here, when John Trelille allegedly became able-bodied after being crippled for 16 years. He was bathed in the waters at the chapel once a week for three weeks, after which time he appeared to be fully healed, and went on to live an active life as a soldier. The very essence of Celtic Christianity, with its powerful Pagan ancestry, seems to be here (Devereux, 1999, pp. 156-157).

Instrument:

Content analysis is an attempt to extract meaning from a “text” by means of carefully defined procedures of categorization (Domhoff, 1996). When applied to dream reports, content analysis attempts to categorize units of meaning so as to obtain data that can be subjected to statistical operations, and/or qualitative analysis.

A previous study had utilized the Strauch Scale (Strauch, 2001), which identifies “magical phenomena,” "paranormal phenomena," and “other bizarre content.” No significant differences were observed between site and home dreams (Krippner, Devereux, & Fish, 2003). Hence, we decided to broaden the scope of our investigation by utilizing the Hall-Van de Castle Scale (1966), one which covers a broader range of dream content items. This instrument contains eight empirically derived categories, most of which are divided into subcategories (Hall & Van de Castle, 1966); subsequent research has demonstrated high intercoder reliability in scoring (Domhoff, 1996).

Method:

The collection of dream reports was supervised by PD. Reports were audio recorded and later transcribed by Dragon Project Trust volunteer assistants. These transcriptions were sent to Stanley Krippner (SK) who had a clerical assistant retype them on standard forms. Following the advice by Domhoff (1996) on content analysis, any report with less than 50 or more than 300 words was eliminated from consideration.

Some volunteers tallied an uneven number of home dreams and site dreams; in these cases, dream reports from the excess side were matched on the basis of length so that the total represented equal numbers of site and home reports. Home dream reports that did not match site dream reports, in terms of word length, were excluded from the study. The rationale for this procedure was that any long dream would be more likely to have the possibility of a content item appearing in it; a very short dream is less likely to contain this content item. All dream reports were matched or eliminated before content scoring was attempted, thus avoiding bias in selection on a content basis.

Seven volunteers contributed 1 pair of reports, ten contributed 2, seven contributed 3, three contributed 4, two contributed 5, four contributed 6, and one contributed 8 pairs of reports. A judge trained in scoring the Hall-Van de Castle Scale evaluated the resulting 204 dream reports, 102 site dreams and 102 matched home dreams. All reports were given code numbers (by SK) so that the judge would not be able to differentiate site dreams from home dreams.

Frequencies of Hall-Van de Castle content categories were computed for all home and all site dream reports then statistically compared along 28 major indices outlined by Domhoff (1996) and summarized in Table 1 using Schneider and Domhoff’s (2003) DreamSAT analysis tool. For some indices (A/C, F/C, and S/C), no effect size or significance test could be computed as the findings are only ratios and not true proportions; the data simply represent numerical differences between one ratio and another. For the data for which statistical tests could be performed, two-tailed tests for statistical differences between two independent proportions (or 2x2 chi-square analysis) was used resulting in a z-score and p value. The n values used to determine effect size and significance for each comparison, are simply the frequencies of each dream element occurring within the series. Cohen's (1977) h- statistic was used to compute effect size. When interpreted correctly, effect size prevents one from regarding small but statistically significant differences as containing important meaning, and conversely prevents disregard for non-significant results that may have a sufficiently large effect size. Domhoff and Schneider’s (1999) extensive review of statistical techniques for dream researchers suggests that for dream research, effect sizes of .40 and above should be considered large, .21 to .40 are moderate, and below .20 are considered small. Since 25 total comparisons were made, it is possible that several comparisons were statistically significant based upon chance alone. Although some researchers (e.g., Domhoff, 1996) advocate using a more conservative alpha level or correction factor, there is no standard or agreed upon method for doing so.

A further exploratory analysis was conducted using the same statistical approach as above to more closely examine how dream reports contributed from each of the four sites compared to the respective matched home reports.

Results:

Overall Results

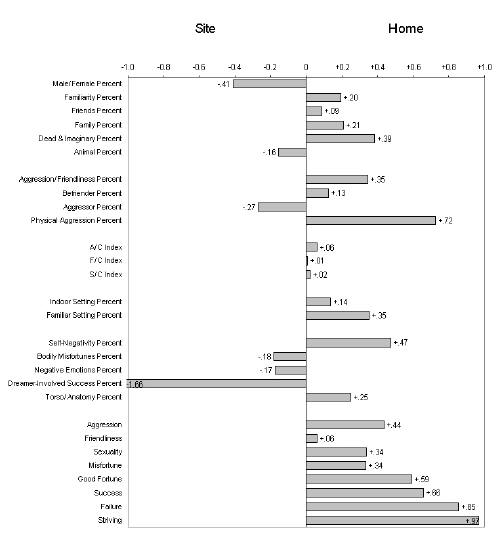

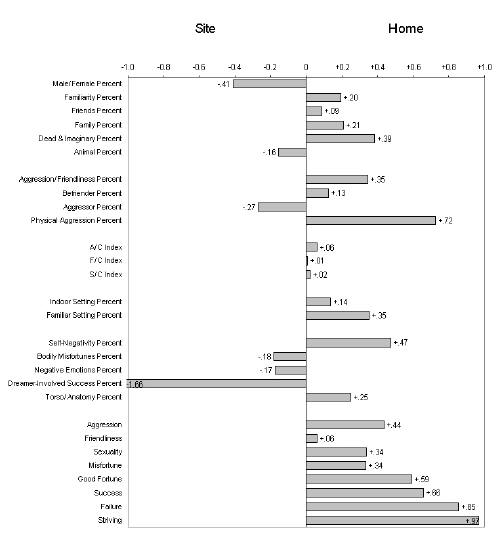

Statistical comparisons between total site dream reports and total matched home dream reports are presented in Table 2, and graphical effect size comparisons are shown in Figure 1. All results are two-tailed, as there was no preconceived direction regarding possible differences. For the "Characters" category, there were two significant differences: The percentage of male characters reported in site dreams was higher (7%) than for matched home dreams (53%), p = .04, with a medium effect size (h = -.29). The percentage of familiar characters was higher in home dream reports (38%) than in site dream reports (28%), p = .025, with a medium effect size (h = .22). Although the percentage of persons identified as “friends” was higher for home dream reports (24%) than for site dream reports (18%), this finding was only a trend (p =.097). There were no significant differences in regards to family members, animal characters, or dead and imaginary characters.

When the "Social Interaction" category was examined, one significant difference emerged: The dreamer was more often identified as the aggressor in aggressive interactions for site dream reports (47%) than for home reports (19%), p = .044, with a large effect size (h = -.62). Although the percentage of physical aggressions was higher for home reports (53%) than for site dream reports (37%), this finding was non-significant (p =.212), but did yield a medium effect size (h = .32). There was no significant finding for percentage of friendly interactions. Ratios for aggressive, friendly, and sexual interactions could not be explored statistically, but an examination of Table 2 reveals no dramatic differences between the two groups.

There were no significant differences between the groups on the environmental settings or self-concept scales. When dream reports with at least one content example of Friendliness, Sexuality, Good Fortune, Success, Failure, and Striving were identified, home dream reports had significantly higher percentages of each item than did site reports, all with medium to large effect sizes. There were no significant differences in regards to aggression and misfortune.

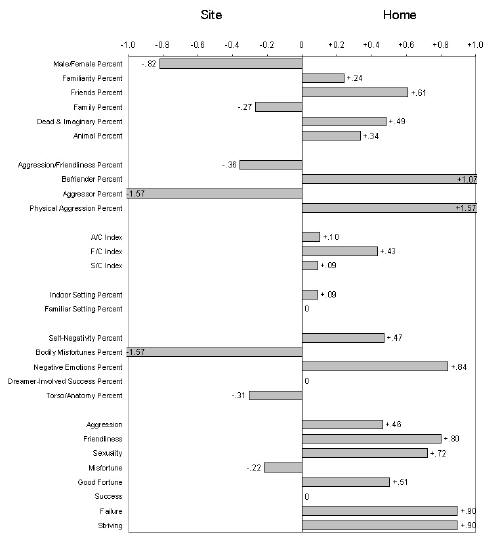

Carn Ingli Results

Statistical comparisons between Carn Ingli site dream reports (n = 35) and matched home dream reports (n = 35) are presented in Table 3, and graphical effect size comparisons are shown in Figure 2. The percentage of reported dead and imaginary characters was significantly higher for matched home dreams when compared to Carn Ingli site dreams, p = .011, with a medium effect size (h = .39). Although there was a higher physical aggression percentage reported in home dreams as compared to Carn Ingli site dreams, this result was non-significant, but did yield a large effect size (h = .72). Similar to the overall results, matched home dreams produced significantly higher percentages of reports with at least one content example of Good Fortune, Success, Failure, and Striving than Carn Ingli site dreams, all with large effect sizes. There was also a nearly significant higher percentage of home dreams reported with at least one Aggression element compared to Carn Ingli site dreams, with a large effect size.

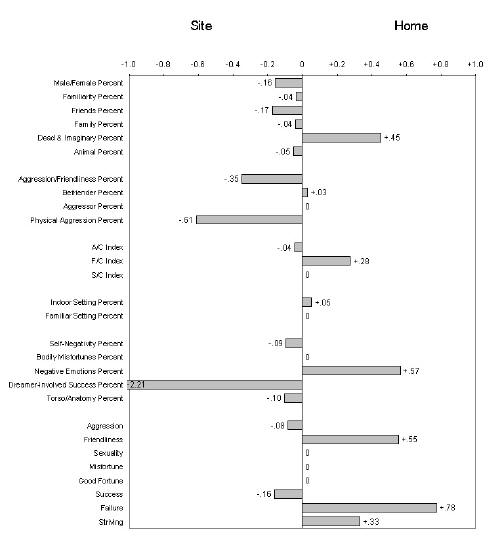

Carn Euny Results

Statistical comparisons between Carn Euny site dream reports (n = 16) and matched home dream reports (n = 16) are presented in Table 4, and graphical effect size comparisons are shown in Figure 3. The percentage of reported male characters was significantly higher for Carn Euny site dreams compared to matched home dreams, p = .020, with a large effect size (h = -.82). In contrast, the percentage of reported friend characters was significantly higher for matched home dreams as compared to the Carn Euny site dreams, p = .021, also with a large effect size (h = .61). Similarly, the percentage of reported dead and imaginary characters was significantly higher for matched home dreams as compared to Carn Euny site dreams, p = .038, with a large effect size (h = .49). Although the Befriender percentage was higher for matched home dream reports than Carn Euny site dream reports, this result was a non-significant trend (p = .098), but did yield a large effect size (h = 1.07). Similar to the overall results, matched home dreams produced significantly higher percentages of reports with at least one content example of Friendliness, Sexuality, Failure, and Striving than Carn Euny site dreams, all with large effect sizes.

Chun Quoit Results

Statistical comparisons between Chun Quoit site dream reports (n = 28) and matched home dream reports (n = 28) are presented in Table 5, and graphical effect size comparisons are shown in Figure 4. The percentage of reported dead and imaginary characters was significantly higher for matched home dreams as compared to Chun Quoit site dreams, p = .006, with a large effect size (h = .45). There was also a higher percentage of Dreamer-Involved Success in Chun Quoit site dreams as compared to matched home dreams, p = .043, with a very large effect size (h = -2.21), although the number of dream reports in this category was quite small. Also, matched home dreams produced significantly higher percentages of reports with at least one content example of Friendliness and Failure than Chun Quoit site dreams, both with large effect sizes.

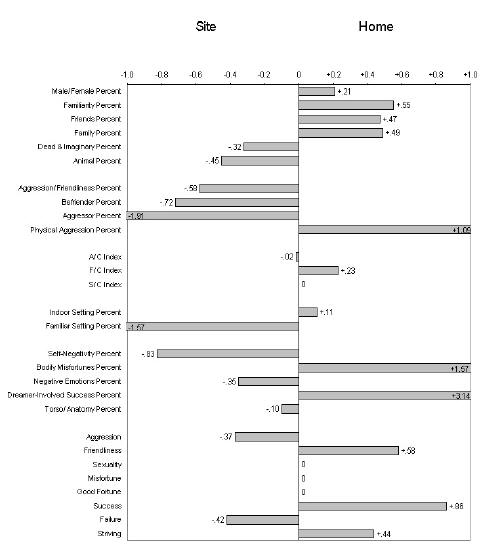

Madron Well Results: Healing and “Feminine Energy”

Statistical comparisons between Madron Well site dream reports (n = 23) and matched home dream reports (n = 23) are presented in Table 6, and graphical effect size comparisons are shown in Figure 5. In contrast to the other sites, the percentage of reported dead and imaginary characters was higher for Madron Well site dreams when compared to matched home dreams. Although this result was only a trend, p = .076, it did yield a medium effect size (h = -.32). The percentage of animal characters was also higher for Madron Well site dream reports as compared to matched home reports, p = .013, and yielded a large effect size (h = -.45). In contrast, percentages of characters scored as familiar, friends, and family were all reported higher for home dream reports than for Madron Well reports (p = .005, p = .015, p = .012 respectively), all yielding large effect sizes (h = .55, h = .47, h = .49 respectively). Although there was a higher Self-Negativity percentage reported for Madron Well site dreams compared to matched home dreams, this result was a non-significant trend (p = .088), but did yield a large effect size (h = -.83). Also, matched home dreams produced significantly higher percentages of reports with at least one content example of Friendliness and Success than Madron Well site dreams, both with large effect sizes.

Traditionally, this site has been associated with “feminine energy,” was a favorite location for “wife women” and their peers. This history underscores the importance of obtaining samples large enough to check for gender differences in future studies. Table 6 indicates that the male/female character ratio was weighted more heavily at Madron Well than at other sites (57% male characters at Madron vs. .64% at Carn Ingli, 71% at Chun Quoit and 80% at Carn Euny)..

Examples:

A customary observation in cosmologies throughout the world is that humans live on one dimension in a tiered cosmos. A transcendent vertical axis mundi connects the other dimensions and transects the ordinary world at special geographies (Campbell, 1974, p. 190). Oftentimes, discontinuity in the landscape –a sudden canyon, a shaft of white quarts, a jagged spire— signals to the adept that an axis mundi is near. The Native Americans of the Columbia River Plateau in the inland Northwest felt that “points of geographic transitions are joined with multiple transitions” in seasonal, individual, and communal cycles (Walker, 1996, p. 67). Thus, ecological transition zones and diurnal times –sunset and sunrise-- are thought to be spiritually auspicious. Where these “points” transect are “especially powerful access points to the sacred” (Ibid.).

Several site dream reports contained elements reminiscent of ancient and mythical Cornwall, for example, “Jurassic rock,” “a cave in the earth,” “a stone tomb,” “a labyrinth,” “a stone circle,” “a cave painting,” “a hag,” and “magicians.” However, a number of home dream reports included similar elements, for example, “fairies,” “a witch,” “a goddess,” “a shamanic initiation,” “a stone tower,” “a big quarry with lots of rocks,” “ancient burial mounts,” and “prehistoric sacred sites.” (These are all excerpts, but are representative of the narratives that these elements summarize.). These examples underscore the necessity of having a standard classification system, such as the Hall-Van de Castle Scale, for purposes of comparison.

Discussion:

The results of this study confirmed the hypothesis. A number of explanations exist for this difference, including expectancy, suggestion, the effect of unfamiliar surroundings, the fact that the selected field sites possessed above-background levels of natural radiation or magnetism, and possible anomalous properties of the sacred sites. However, several limitations are obvious. In the first place, volunteers contributed unequal numbers of dream reports. However, if each volunteer had been limited to one pair, insufficient data for statistical analysis would have been available.

Several steps could be taken to narrow down the available explanations. The effects of expectancy and suggestion could be reduced by having volunteers dream in one or more “control sites,” i.e., outdoor locations equally as interesting as the “sacred sites,” but locations with no history of ritual use by indigenous people (see Houran & Brugger, 2000). The possible impact on dream content of sleeping in unfamiliar surroundings (see Okuma, Fukuma, & Kobayashi, 1975) could be reduced by allowing volunteers to spend some time at the outdoor sites during daytime. In addition, investigators could randomize the order in which they slept at home with the nights spent at the sites.

Without these modifications, the differences observed in this study could be attributed to "indoor" vs. "outdoor" dreaming. For example, "outdoor" dreaming exposes the dreamer to unknown agencies, and aggression could be attributed to most of them. The aggressor might be perceived as male, and this would explain the significant difference found in the male/female ratio.

One would expect that home dream reports would include more familiar persons and friends. One would also expect that home dreams would include more content items of any type given the familiar surroundings (Hall & Van de Castle, 1966: Krippner & Weinhold, 2002). The difference between the two groups illustrating this phenomenon is apparent in Table 2. Future investigation needs to focus upon cross-cultural differences concerning the impact of outdoor sites upon dream content, the impact of the length of dream reports on content analysis in various settings, gender differences in studies of this nature, and the influence of local traditions upon dream content (as in the reputed “feminine energy” associated with Madron Well in this study). The investigations of Kuiken and his associates on dream metaphors (Kuiken, 1999), movement inhibition during dreaming (Kuiken, Busnik, Dukewich, & Gendlin, 1996), and transcendent and impactful dreams (Kuiken, 1995; Kuiken & Nielsen, 1990) all contain related data that would lend depth to future investigations of dreaming in alleged sacred locations. There are additional scales that would also be of value, e.g., the Casto Spirituality Scoring System (Casto, Krippner, & Tartz, 1999).

In addition, previous anthropological work could be adapted to this type of study. For example, Lewis-Williams (1998) proposed that some images reported from altered states of consciousness are cross-culturally similar. He has delineated three stages in the development of imagery, based on laboratory studies and experiential reports. “Luminous, pulsating, enlarging, fragmenting and changing geometric forms” constitute the first stage. The second set stage includes, “grids, dots, zigzags, nested catenary curves and sets of parallel lines,” while the third (and deepest) stage contains “iconic hallucinations” of animals, people, and monsters (p. 163). Where Lewis-Williams used this instrument in archaeology to categorize pictographs, we would suggest using it in an archaeological context to categorize dream reports.

There were several reports reminiscent of Lewis-Williams first stage; one dreamer reported, “I started to see … red lights…flashing backwards and forwards and I felt … I was losing it.” Another thought that she was in a “channel or passageway, with buzzing coming at me from both sides.” For both, the input (lights and sounds) consumed the dreamer’s sensorium. A dream report of “black and white stripes” is reminiscent of Lewis-Williams’ second stage, while “a tall white robed figure guarding a gate” in another dream report exemplifies the third (or “iconic”) stage.

Conclusion:

This investigation attempted to make a modest contribution to the study of natural environmental influences on dreams, which is a much needed addition to previous research that has focused on dream content influenced by the built environment. Although some of the differences between sacred site dreaming and dreaming in familiar surroundings were statistically significant, these differences were modest. However, the same could be said for earlier studies that explored the impact of presleep experiences and external stimulation on the content of dream reports. If this line of inquiry evokes interest on the part of other investigators, there are many improvements that could be made and many areas that remain unexplored. The notion of sacred sites reflects a unity of human beings and their natural environment, a union that has been virtually forgotten in modern times, but one that is well worth reestablishing.

Here again, this revival of rituals and beliefs that reflect a psycho-spiritual bond between humans and nature harks back to our introductory comments. Specifically the Greeks had two terms for place, topos and chora. Topos signifies a simple location, the physical, observable features of a locale. Chora, however, refers to the more subtle aspects of place, those that can trigger memory, imagination, and mythic presence (Devereux, 1997). In the Timaeus, Plato claimed that chora could be known “in a kind of dream” (Lee, 1965). People who thought that they were in touch with chora as well as topos built sacred sites. One way to study a sacred site is to attempt approximating the mind-frame of the builders and users of the site. In accordance with our hypothesis, nighttime dreaming might put dreamers in touch with what David Feinstein (2000) refers to as the “mythic field” of these sites, the “stored” information of a “field” that may be accessed during altered states of consciousness (Devereux, 1990).

Moreover, the broader implications of our hypothesis shares the concerns of ecopsychologists (e.g., Larsen, 1995; Roberts, 1998), Devereux (1997) whose conceptual orientation dovetails with an area of inquiry now officially termed “cognitive archaeology;” a perspective that may result in healing the estrangement of Western scholars from their environment. In addition to studying landscapes with maps, aerial photographs, satellite imagery, and other instruments that establish and perpetuate a distance between subject and object, they might develop an appreciation of the imaginative, expressive qualities of place. This perspective is a much needed antidote, because currently “[w]herever the Western mind goes, it marginalizes local, indigenous, and often, very different worldviews and systems of knowledge” (p. 530). Indeed, western science has adopted a particular cognitive model, one that takes a different cognitive perspective of its surroundings than do indigenous models, but one that is “not necessarily superior” (p. 531). Visiting, studying, and spending time at sacred sites (as well as sleeping and dreaming there) serve as reminders that one’s state of consciousness and one’s view of the land inevitably relate to one another.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Robert L. Van de Castle for his helpful suggestions, Andrew Delpino and Steve Hart for clerical and editorial support, Marena Koukis for serving as judge, and Robert Tartz for his statistical analysis of the data. They are also grateful to Gabrielle Hawkes, who transcribed the bulk of the audio-recorded dream reports as well as facilitating many of the on-site sessions. Finally, thanks are due to the volunteer dreamers and their helpers, without whom there would be no “sacred site” dream data to analyze. This study was supported by Saybrook’s Chair for the Study of Consciousness, and by the Dragon Project Trust. Some of the material included in this article was published earlier in ReVision and Dreaming journals, but this article is the only one to present a complete analysis of the data...

References:

Antrobus, J. (1993). Characteristics of dreams. In M.A. Carskadon (Ed.), Encyclopedia of sleep and dreaming (pp. 98-101). New York: Macmillan.

Busnik, R., & Kuiken, D. (1995). Identifying types of impactful dreams: A replication. Dreaming, 6, 97- 119.

Campbell, J. (1974). The mythic image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carmichael, D. (1994). Places of power: Mescalero Apache sacred sites and sensitive areas. In D. Carmichael, J. Hubert, B. Reeves, & A. Schanche (Eds.), Sacred sites, sacred places (pp. 90-98). London: Routledge.

Cartwright, R.D., Berniche, N., Borowitz, G., & Kling, G. (1969). Effect of an erotic movie on sleep and dreams of young men. Archives of General Psychiatry, 20, 163-271.

Casto, K.K., Krippner, S., & Tartz, R. (1999). The identification of spiritual content in dream reports. Anthropology of Consciousness, 10, 43-53.

Cook, I.A. (2003). Ancient Acoustic Resonance Patterns Influence Regional Brain Activity. ICRL Internal Technical Report. Princeton: International Consciousness Research Laboratories.

Crumley, C. (1999). Sacred Landscapes: Constructed and Conceptualized. In W. Ashmore & A. Knapp (Eds.), Archaeologies of Landscape (pp. 269-276). Oxford: Blackwell.

Deloria, V., Jr. (2000). Reflection and revelation: Knowing land, places and ourselves. In J.A. Swan (Ed.), The power of place and human environments (pp. 28-40). Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Dement, W., & Wolpert, E.A. (1956). The relation of eye movements, body motility, and external stimuli to dream content. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55, 543-553.

Devereux, P. (1990). Places of power: Measuring the secret energy of ancient sites. London: Blandford.

Devereux, P. (1992). Secrets of ancient and sacred places: The world’s mysterious heritage. London: Blandford.

Devereux, P. (1997). The archaeology of consciousness. Journal for Scientific Exploration, 4, 527-538.

Devereux, P. (1999). Places of power: Measuring the secret energy of ancient sites (2nd ed.). London: Cassell.

Devereux, P. (2000). The Sacred Place. London: Cassell.

Devereux, P. (in press). Ears and Years: Acoustics and Intentionality in Antiquity. In C. Scarre & G. Lawson (Eds.), Archaeoacoustics. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Devereux, P., Steele, J., & Kubrin, D. (1989). Earthmind. New York: Harper & Row.

Domhoff, G. W. (1996). Finding meaning in dreams: A quantitative approach. New York: Plenum.

Eck, D. (1981). India's Tirthas: Crossings in sacred geography. History of Religions, 20, 323-344.

Feinstein, D. (2000). At play in the fields of the mind: Personal myths as fields of information. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 38, 71-109.

Foulkes, D., Belvedere, E., Masters, R.E.L., Houston, J., & Krippner, S. (1972). Long-distance “sensory bombardment” ESP in dreams: A failure to replicate. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 35, 731-734.

Foulkes, D., & Rechtschaffen, A. (1964). Presleep determination of dream content: Effects of two films. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 19, 983-1005.

Hale, J.R., de Boer, J.Z., Chanton, J.P., & Spiller, H.A. (200, July 13). Questioning the Delphic Oracle. Scientific American, 1-5.

Hall, C., & Van de Castle, R.L. (1966). The content analysis of dreams. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Houran, J., & Brugger, P. (2000). The need for independent control sites: A methodological suggestion with special reference to haunting and poltergeist field research. European Journal of Parapsychology, 15, 30-45.

Jahn, R.G., Devereux, P., & Ibison, M. (1996). Acoustical resonances of assorted ancient structures. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 99, 2, 649-658.

Krippner, S., & Bova, M. (1974). Environmental influences on clairvoyance and alterations in consciousness. International Journal of Paraphysics, 8, 48-56.

Krippner, S., Devereux, P., & Fish, A. (2003). The use of the Strauch Scale to study dream reports from sacred sites in England and Wales. Dreaming, 13, 95-105.

Krippner, S., Honorton, D., Ullman, M., Masters, R.E.L., & Houston, J. (1971). A long-distance “sensory bombardment” study of ESP in dreams. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 65, 469-475.

Krippner, S., & Thompson, A. (1996). A 10-facet model of dreaming applied to dream practices of sixteen Native American cultural groups. Dreaming, 6, 71-96.

Krippner, S., & Weinhold, J. (2002. Gender differences in a content analysis study of 608 dream reports from research participants in the United States. Social Behavior and Personality, 30, 399-409.

Kuiken, D. (1995). Dreams and feeling realization. Dreaming, 5, 129-157.

Kuiken, D. (1999). An enriched conception of dream metaphor. Sleep and Hypnosis, 1, 112-121...

Kuiken, D., Busnik, R., Dukewich, T.L., & Gendlin, E.T. (1996). Individual differences in or from concurrent reports of movement inhibition, Dreaming, 6, 251-157.

Kuiken, D., & Smith, L. (1991). Impactful dreams and metaphor generation, Dreaming, 1, 135-145.

Larsen, S. (1995, Spring). Ecology and the archaic psyche. Psyche: The Ecopsychology Newsletter, p. 3.

Lee, D. (Ed. & Trans.). (1965). Plato: Timaeas and Critia. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. (1998). Wrestling with analogy: A methodological dilemma in Upper Paleolithic art research. In D.S. Whitley (Ed.), Reader in archaeology theory: Post-processual and cognitive approaches (pp.157-179). New York: Routledge.

Okuma, T., Fukuma, E., & Kobayashi, R. (1975). Dream detector and comparison of laboratory and home dreams by REM awakening technique. In E.D. Weitzman (Ed.), Advances in sleep research (Vol. 2, pp. 223-231). New York: Spectrum.

Otto, R. (1924). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rechtschaffen, A., & Foulkes, D. (1965). Effect of visual stimuli on dream content. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 20, 1148-1160.

Roberts, E.J. (1998). Place and the human spirit. The Humanistic Psychologist, 26,

5-34.

Roussy, F., Brunette, M., Mercier, P., Gonthier, I., Grenier, J., Sirois-Berliss, M., Lortie-Lussier, M., De Koninck, J. (2000). Daily events and dream content: Unsuccessful matching attempts. Dreaming, 10, 77-83.

Schneider, A. & Domhoff, G.W. (2003). DREAMSAT. Retrieved April 13, 2005, from http://psych.ucsc.edu/dreams/DreamSAT/index.html

Sheeran, P.F. (1990). Place and power. ReVision, 13, 28-32.

Strauch, I. (2001). Magische und paranomale Phänomene in Träumen [Magical and paranormal phenomenable in dreams]. In E. Rüther, A. Gruber-Rüther, & M. Heuser (Eds.), Träume [Dreams] (pp. 355-364). Innsbruck, Austria: VIP-Verlag Integrative Psychiatrie.

Swan, J. (1988). Sacred places in nature and transpersonal experience. ReVision, 10, 21-26.

Walker, D.E. (1996). Durkheim, Eliade, and sacred geography in Northwestern North America. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers, 52, 63-68. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon.

Witkin, H., & Lewis, H. (1963). The relationship of experimentally induced pre-sleep experiences to dreams: A report on method and a preliminary finding. Journal of the American Psychoanalytical Association, 13, 819-849.

Table 1

Formulas used in DreamSAT to compute scores for major content categories

|

Dream Content Index |

Equation (Hall-Van de Castle Elements) |

| Characters |

| 1 |

Male/Female Percent |

Males / (Males + Females) |

| 2 |

Familiarity Percent |

Familiar / (Familiar + Unfamiliar) |

| 3 |

Friends Percent |

Friends / All humans |

| 4 |

Family Percent |

(Family + Relatives) / All humans |

| 5 |

Dead & Imaginary Percent |

(Dead + Imaginary characters) / All characters |

| 6 |

Animal Percent |

Animals / All characters |

| Social Interaction Percents |

| 1 |

Aggression/Friendliness Percent |

Dreamer-involved Aggression / (D-inv. Aggression + D-inv. Friendliness) |

| 2 |

Befriender Percent |

Befriender / (Befriender + Befriended) |

| 3 |

Aggressor Percent |

Aggressor / (Aggressor + Victim) |

| 4 |

Physical Aggression Percent |

Physical aggressions / All aggressions |

| Social Interaction Ratios |

| 1 |

A/C Index |

All aggressions / All characters |

| 2 |

F/C Index |

All friendliness / All characters |

| 3 |

S/C Index |

All sexuality / All characters |

| Settings |

| 1 |

Indoor Setting Percent |

Indoor / (Indoor + Outdoor) |

| 2 |

Familiar Setting Percent |

Familiar / (Indoor + Outdoor) |

| Self-Concept Percents |

| 1 |

Self-Negativity Percent |

(D as Victim + D-involved Misfortune + D-involved Failure) /

(D as Victim + D-inv. Misfortune + D-inv. Failure + D as Befriended +

D-inv. Good Fortune + D-inv. Success) |

| 2 |

Bodily Misfortunes Percent |

Bodily misfortunes / All misfortunes |

| 3 |

Negative Emotions Percent |

Negative emotions / All emotions |

| 4 |

Dreamer-Involved Success Percent |

D-involved Success / (D-involved Success + D-involved Failure) |

| 5 |

Torso/Anatomy Percent |

Torso, Anatomy, Sex body parts / All body parts |

| Percentage of Dreams with at Least One: |

| 1 |

Aggression |

Dreams with aggression / Number of dreams |

| 2 |

Friendliness |

Dreams with friendliness / Number of dreams |

| 3 |

Sexuality |

Dreams with sexuality / Number of dreams |

| 4 |

Misfortune |

Dreams with misfortune / Number of dreams |

| 5 |

Good Fortune |

Dreams with good fortune / Number of dreams |

| 6 |

Success |

Dreams with success / Number of dreams |

| 7 |

Failure |

Dreams with failure / Number of dreams |

| 8 |

Striving |

Dreams with success OR failure / Number of dreams |

Table 2

Comparisons between all home dreams and all site dreams (N = 204)

| Dream Content Index |

"Home Dreams" series |

"Site Dreams" series |

Effect size

(h) |

p |

N for "Home Dreams" |

N for

"Site Dreams" |

| Characters |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male/Female Percent |

53% |

67% |

-.29 |

* .040 |

110 |

88 |

| Familiarity Percent |

38% |

28% |

+.22 |

* .025 |

250 |

190 |

| Friends Percent |

24% |

18% |

+.16 |

.097 |

250 |

190 |

| Family Percent |

08% |

05% |

+.13 |

.162 |

250 |

190 |

| Dead & Imaginary Percent |

04% |

03% |

+.09 |

.309 |

294 |

239 |

| Animal Percent |

12% |

16% |

-.11 |

.227 |

294 |

239 |

| Social Interaction Percents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aggression/Friendliness Percent |

34% |

42% |

-.16 |

.384 |

88 |

48 |

| Befriender Percent |

60% |

56% |

+.08 |

.729 |

52 |

27 |

| Aggressor Percent |

19% |

47% |

-.62 |

* .044 |

27 |

17 |

| Physical Aggression Percent |

53% |

37% |

+.32 |

.212 |

36 |

27 |

| Social Interaction Ratios |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A/C Index |

.12 |

.11 |

+.02 |

|

294 |

239 |

| F/C Index |

.23 |

.14 |

+.21 |

|

294 |

239 |

| S/C Index |

.01 |

.00 |

+.02 |

|

294 |

239 |

| Settings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indoor Setting Percent |

48% |

43% |

+.09 |

.571 |

113 |

69 |

| Familiar Setting Percent |

79% |

86% |

-.18 |

.568 |

33 |

14 |

| Self-Concept Percents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Self-Negativity Percent |

60% |

58% |

+.05 |

.792 |

88 |

33 |

| Bodily Misfortunes Percent |

30% |

33% |

-.07 |

.834 |

20 |

15 |

| Negative Emotions Percent |

85% |

83% |

+.06 |

.797 |

55 |

30 |

| Dreamer-Involved Success Percent |

43% |

67% |

-.47 |

.443 |

23 |

3 |

| Torso/Anatomy Percent |

21% |

21% |

+.00 |

.975 |

80 |

95 |

| Dreams with at Least One: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aggression |

23% |

18% |

+.12 |

.382 |

102 |

102 |

| Friendliness |

43% |

24% |

+.42 |

** .003 |

102 |

102 |

| Sexuality |

03% |

00% |

+.34 |

* .014 |

102 |

102 |

| Misfortune |

19% |

15% |

+.11 |

.452 |

102 |

102 |

| Good Fortune |

04% |

00% |

+.40 |

** .004 |

102 |

102 |

| Success |

13% |

03% |

+.39 |

** .006 |

102 |

102 |

| Failure |

13% |

01% |

+.53 |

** .000 |

102 |

102 |

| Striving |

25% |

04% |

+.64 |

** .000 |

102 |

102 |

Figure 1

Effect size (h) comparisons between all home dreams and all site dreams

click image to enlarge

Table 3

Comparisons between matched home dreams and Carn Ingli site dreams (N = 70)

|

Dream Content Index

|

"Home Dreams" series |

"Site Dreams" series |

Effect size

(h) |

p |

N for "Home Dreams" |

N for

"Site Dreams" |

| Characters |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male/Female Percent |

43% |

63% |

-.41 |

.138 |

42 |

19 |

| Familiarity Percent |

38% |

29% |

+.20 |

.250 |

94 |

55 |

| Friends Percent |

26% |

22% |

+.09 |

.607 |

94 |

55 |

| Family Percent |

09% |

04% |

+.21 |

.220 |

94 |

55 |

| Dead & Imaginary Percent |

04% |

00% |

+.39 |

* .011 |

109 |

72 |

| Animal Percent |

10% |

15% |

-.16 |

.302 |

109 |

72 |

| Social Interaction Percents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aggression/Friendliness Percent |

41% |

25% |

+.35 |

.253 |

34 |

16 |

| Befriender Percent |

56% |

50% |

+.13 |

.743 |

16 |

12 |

| Aggressor Percent |

21% |

33% |

-.27 |

.673 |

14 |

3 |

| Physical Aggression Percent |

60% |

25% |

+.72 |

.098 |

15 |

8 |

| Social Interaction Ratios |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A/C Index |

.14 |

.11 |

+.06 |

|

109 |

72 |

| F/C Index |

.21 |

.21 |

+.01 |

|

109 |

72 |

| S/C Index |

.01 |

.00 |

+.02 |

|

109 |

72 |

| Settings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indoor Setting Percent |

47% |

40% |

+.14 |

.579 |

47 |

25 |

| Familiar Setting Percent |

86% |

71% |

+.35 |

.446 |

14 |

7 |

| Self-Concept Percents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Self-Negativity Percent |

65% |

42% |

+.47 |

.146 |

43 |

12 |

| Bodily Misfortunes Percent |

25% |

33% |

-.18 |

.713 |

12 |

6 |

| Negative Emotions Percent |

84% |

90% |

-.17 |

.656 |

19 |

10 |

| Dreamer-Involved Success Percent |

45% |

100% |

-1.66 |

.112 |

11 |

1 |

| Torso/Anatomy Percent |

28% |

17% |

+.25 |

.342 |

29 |

29 |

| Dreams with at Least One: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aggression |

29% |

11% |

+.44 |

.067 |

35 |

35 |

| Friendliness |

37% |

34% |

+.06 |

.803 |

35 |

35 |

| Sexuality |

03% |

00% |

+.34 |

.155 |

35 |

35 |

| Misfortune |

31% |

17% |

+.34 |

.159 |

35 |

35 |

| Good Fortune |

09% |

00% |

+.59 |

* .013 |

35 |

35 |

| Success |

23% |

03% |

+.66 |

** .006 |

35 |

35 |

| Failure |

17% |

00% |

+.85 |

** .000 |

35 |

35 |

| Striving |

37% |

03% |

+.97 |

** .000 |

35 |

35 |

Figure 2

Effect size (h) comparisons between matched home dreams and Carn Ingli site dreams

click image to enlarge

Transformation of one sort or another was sought through the practice of “temple sleep” in a place of worship or in a venerated natural site, with the aim of “incubating” dreams for initiation, divination, or healing purposes. Ancient Jewish seers would spend the night in a grave or sepulchral vault, hoping that the spirit of the deceased would appear in a dream and offer information of guidance. Chinese incubation temples, where state officials would seek guidance, were active until the 16th century. In Japan, the emperor had a dream hall in his palace where he would sleep on a polished stone bed when he needed assistance in resolving a matter of state. Dynastic Egypt had special temples for suppliants who would fast and recite prayers immediately before going to sleep. Before Thutmose IV (c. 1419-1386 PCE) became ruler of Egypt, he related how the god Hormakhu appeared in a dream, foretelling of a united kingdom that would follow his ascension to power. When this came to pass, Thutmose IV recorded the dream on a pillar of stone that still stands before the Sphinx. Temple sleep was also was popular in ancient Greece where over 300 dream temples were dedicated to Aesculapius, the god of healing (Devereux, 2004).

Transformation of one sort or another was sought through the practice of “temple sleep” in a place of worship or in a venerated natural site, with the aim of “incubating” dreams for initiation, divination, or healing purposes. Ancient Jewish seers would spend the night in a grave or sepulchral vault, hoping that the spirit of the deceased would appear in a dream and offer information of guidance. Chinese incubation temples, where state officials would seek guidance, were active until the 16th century. In Japan, the emperor had a dream hall in his palace where he would sleep on a polished stone bed when he needed assistance in resolving a matter of state. Dynastic Egypt had special temples for suppliants who would fast and recite prayers immediately before going to sleep. Before Thutmose IV (c. 1419-1386 PCE) became ruler of Egypt, he related how the god Hormakhu appeared in a dream, foretelling of a united kingdom that would follow his ascension to power. When this came to pass, Thutmose IV recorded the dream on a pillar of stone that still stands before the Sphinx. Temple sleep was also was popular in ancient Greece where over 300 dream temples were dedicated to Aesculapius, the god of healing (Devereux, 2004).

Madron Well, likewise in Land’s End, was once surrounded by massive blocks of granite (according to a 1910 photograph) and is located near the ruins of a medieval granite chapel. The footpath through the woods is like a magical, green-hued walk redolent of former times and beliefs. By the time the visitor reaches the turning for the well on the left, the 20th century seems far away. Traditionally, this site has been associated with “feminine energy.” Up until about the 17th century, a local “wise woman” attended the actual spring. The spring water continues to be fed by stone conduit into a stone reservoir in the chapel’s southwest corner. Madron Well was celebrated for its purported healing properties and oracular powers, and part of the traditional healing procedure involved the patient sleeping within the chapel, one of the few documented cases of ostensibly Christian dream incubation in England. Presumably because it passes through granite conduits, and is deposited into a granite reservoir, the water gives above-background radiation readings. In the 1600s a celebrated and documented case of healing took place here, when John Trelille allegedly became able-bodied after being crippled for 16 years. He was bathed in the waters at the chapel once a week for three weeks, after which time he appeared to be fully healed, and went on to live an active life as a soldier. The very essence of Celtic Christianity, with its powerful Pagan ancestry, seems to be here (Devereux, 1999, pp. 156-157).

Madron Well, likewise in Land’s End, was once surrounded by massive blocks of granite (according to a 1910 photograph) and is located near the ruins of a medieval granite chapel. The footpath through the woods is like a magical, green-hued walk redolent of former times and beliefs. By the time the visitor reaches the turning for the well on the left, the 20th century seems far away. Traditionally, this site has been associated with “feminine energy.” Up until about the 17th century, a local “wise woman” attended the actual spring. The spring water continues to be fed by stone conduit into a stone reservoir in the chapel’s southwest corner. Madron Well was celebrated for its purported healing properties and oracular powers, and part of the traditional healing procedure involved the patient sleeping within the chapel, one of the few documented cases of ostensibly Christian dream incubation in England. Presumably because it passes through granite conduits, and is deposited into a granite reservoir, the water gives above-background radiation readings. In the 1600s a celebrated and documented case of healing took place here, when John Trelille allegedly became able-bodied after being crippled for 16 years. He was bathed in the waters at the chapel once a week for three weeks, after which time he appeared to be fully healed, and went on to live an active life as a soldier. The very essence of Celtic Christianity, with its powerful Pagan ancestry, seems to be here (Devereux, 1999, pp. 156-157).